The Genesis of the Italian Madrigal

From the frottola to the madrigal, and two early madrigalists

If I were to pick a favourite form of music, it must be the Italian madrigal: a form of secular, vernacular poetry set to music. flourishing in the 16th and 17th centuries, it spread far and wide across Europe, adopting and evolving across time in various countries. Indeed, the word ‘madrigal’ meant one thing to a Venetian in 1490, another to a Burgundian in 1530, something else to a Roman in 1590, even more different to an early 17th century Englishman, and was an entirely new species in its concerted form by the end of Claudio Monteverdi’s career in the 1640s. While a full history of the madrigal is beyond the scope of one blogpost, its colorful genesis makes for a pithy and curious tale. This post is a reworking of my final paper for a college course on the Italian Renaissance (more on that one day).

Musicologist Alfred Einstein argues Italy barely had any role in musical development in the 15th century. Even in the early 16th century, nobles, dukes, and republics across the patchwork of states constituting what is now Italy imported their musicians and composers from France, Burgundy, and the Holy Roman Empire. One such composer was Heinrich Isaac (1450–1517), acquired by Lorenzo de’ Medici of Florence around 1475. Isaac was partly in charge of Lorenzo’s children’s education. He wrote many motets, mass settings, and secular precedents of the madrigal, like the chanson– a fairly common oeuvre for the 15th century composer. Another such secular form, the frottola, typically used three to four voices in a homophonic (rhythmically aligned) texture. In it, the melody was often sung alone, accompanied by instruments such as lute.

A key figure in developing the frottola into the madrigal was Pietro Bembo (1470–1547)— poet, literary scholar, humanist, classicist, member of the Knights Hospitaller, diplomat, and later cardinal. Bembo defended the vernacular as appropriate for literature and poetic language, fixating on the synthesis of poetry through sound, rhythm, and meaning. This sparked a re-examination of the medieval works of Petrarch and Boccaccio, with Bembo taking their written form as his vernacular base. Words, in this new theory, did not mean mere names or descriptors or labels. Their sounds, rhythms, and meanings were vital in how they fit into poetry. Music, therefore, was not an ornamental accompaniment to be slapped onto the text; it dealt directly with this new role for words. Gone was the frolicky frottola style, replaced by a more serious style dealing with a larger range of meaning and emotion. Polyphonic music used by northern Europeans, especially those in the Franco-Flemish school of modern-day France and Belgium, leant itself much more cleanly to this new form of text. Thus was the madrigal born– a product of gradual change and not an overnight transformation. Einstein describes the musical changes:

“Compared with the frottola, the harmonies of the madrigal begin to assume a fluctuating and labile character. No longer are the voices of unequal importance; each voice now claims a fairly equal share in the musical structure, though without prejudice to the special rights of the soprano as the highest part and the one most prominently heard, and of the bass, which supports the whole. The “accompanied monody” becomes a work of art for several voices. The closed song form gives way to the free motet form. Wherever this new structure was applied to a “free” text, for example a canzone stanza, a ballata, or a true madrigal text, we have the genuine madrigal as a textual-musical concept.”

Culturally, the madrigal was a common feature in high society, as chamber music for entertainment. As its form gained popularity, the madrigal’s presence expanded to wedding ceremonies, private and public celebrations, and intermediary performances in dramas. Einstein emphasizes the importance of smaller, restrained forces singing softly and bringing out textual meaning– large choruses are counterproductive. There was no ‘conductor’; all singers were at equal footing and except for performance in festive music, most likely one singer per part. This helped bring out dissonances (which were employed more frequently than in sacred music) more effectively. To be a court singer in the Italian Renaissance was a position of great responsibility; singers needed to be familiar with theory, text, and declamatory styles. This independence and self-reliance for one’s own vocal part in secular madrigals would bring the development of monodies, virtuosic solo pieces with accompaniment, at the turn of the 17th century.

Philippe Verdelot (1480/85–1530/40) found himself in this rapidly developing cultural environment after moving to Italy from his native southern France in his early years. Giorgione’s famous painting The Three Ages of Man (~1500–05) depicts Verdelot on the right side with a beard. Einstein traces its history to prove that Verdelot was active in Venice at that time. A letter from May 1521, from papal chaplain Niccolò de Pitti to Cardinal Giuliano de Medici (later Pope Clement VII), places Verdelot as just having arrived in Florence in 1521. In it, de Pitti recommends that the Cardinal employ Verdelot, and urges for a high salary– this establishes him as a composer of considerable talent, worthy of the patronage of the wealthier-than-thou Medici family. Verdelot’s madrigals, re-printed many times over even after his death, establish him as a successful and sought-after composer. His madrigals have a strong basis in homophony, though degrees of polyphonic freedom seep in with time. The choice of texts and Verdelot’s musical treatment sometimes vary by intended audience or setting, with more elegant texts and less rigid musical styles used for elevated Florentine audiences and quasi-operatic styles rich with a blend of homophony and polyphony for intermezzi in plays.

Linked below is an album of his madrigals recorded by the group Profeti della Quinta, and an Early Music Sources video analysis of his madrigal Con soave parlar. Another favorite Verdelot madrigal is his setting of the first stanza of Petrarch’s magnificent Italia mia, one of the earliest examples of Italian nationalism. This beautiful madrigal deserves a post to itself.

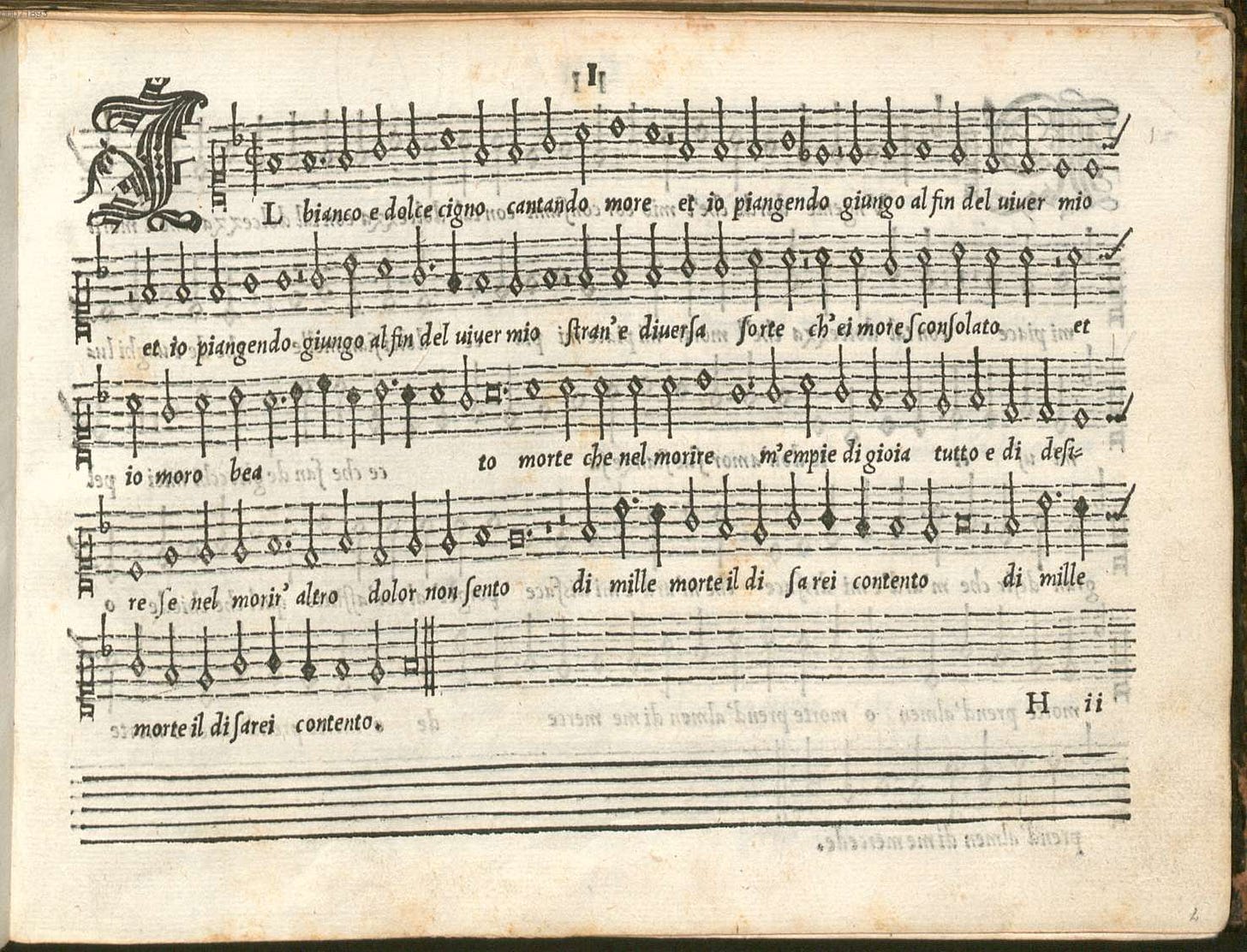

Verdelot’s musical influence was reflected in the next generation of madrigalists, chief among which was Jacques Arcadelt (1507–68). Born in Liége, he made his way to Florence, where Einstein places him before 1539 based on a dirge written at the death or departure of a Florentine and published in his Third Book of Madrigals (1544). Given they worked in the same field in the same city at about the same time, it is very plausible to hypothesize a meeting or even collaboration between Arcadelt and Verdelot. It was also in 1539 that Arcadelt’s First Book of Madrigals was reprinted. This volume contains the most famous single piece of the 16th century, Il bianco e dolce cigno (The white and sweet swan)– indeed, it was reprinted many times, appearing in collections as far in time and space as England in 1612. Even the esteemed Claudio Monteverdi published Arcadelt’s madrigals in 1627, nearly a century after they were first written. Also skilled in writing sacred music, Arcadelt served in the Sistine Chapel in the 1540s, and eventually returned to France. Musically, his work cements the stylistic changes developed by Verdelot and popularizes the four-voice madrigal.

The Italian madrigal is special to me. My first experience of choral singing was in the University of Chicago’s Early Music Ensemble (EME) in my first year of college. That year, we featured the Italian madrigal, working our way from Verdelot and Arcadelt to Willaert and Cipriano de Rore and finally reaching Gesualdo and Monteverdi before the pandemic sent us all home. During the EME open house in September 2019, we sight-sang Il bianco e dolce cigno, and it remains a favorite of mine.

Personal fondness of the genre aside, the story of the madrigal makes me smile knowing how all art and literature and culture are connected, inseparable from one another. How else would a man of many talents like Pietro Bembo wright a new genre into existence? Would he have known this would be the result of his literary reinterpretations? Musical innovation, for the large part, has always been anchored firmly in the embrace of the past. I say it is for the better; new for new’s sake leads us to forget why we cherish the arts we currently enjoy. The madrigalists had their Petrarchs and Boccaccios, and we have our own white and sweet swans to emulate in our art.

Music referenced here:

Verdelot, Madrigals for Four Voices ( recorded by Profeti Della Quinta): Spotify | Apple | YouTube

Verdelot, Madrigals, including Italia mia: Spotify | Apple | YouTube

Arcadelt, Il bianco e dolce cigno: Spotify | Apple | YouTube

References

Einstein, Alfred. 1949. The Italian Madrigal. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Fischer, Kurt von, Gianluca D’Agostino, James Haar, Anthony Newcomb, Massimo Ossi, Nigel Fortune, Joseph Kerman, and Jerome Roche. "Madrigal." Grove Music Online. 2001.

Mace, Dean T. 1969. "Pietro Bembo and the Literary Origins of the Italian Madrigal." The Musical Quarterly (Oxford University Press) 55 (1): 65-86.

Sherr, Richard. 1984. "Verdelot in Florence, Coppini in Rome, and the Singer "La Fiore"." Journal of the American Musicological Society (University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society) 37 (2): 402-411.