In the first post of this series, we discussed the dilapidating state of Italian opera around the turn of the 19th century and underscored the key differences between the Classicist and Romanticist camps– chiefly that the Romantics fundamentally disagreed with the Classicist conception of opera being based in ancient history and mythology, arguing instead of more contemporaneous settings influenced by history in the Christian era and modern religiosity. Musically, the Romanticists wanted to craft a new genre of dramma per musica instead of stale poetry and rambunctious arias thrown together in a motley crew of numbered, sequential movements. Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872) wanted composers to employ an “authentic local color” in their music, along with appealing to the uniqueness of different characters through melodic means.

Now, a closer understanding of German and Italian theories of form will prepare us to bridge the nexus through Giuseppe Verdi’s music.

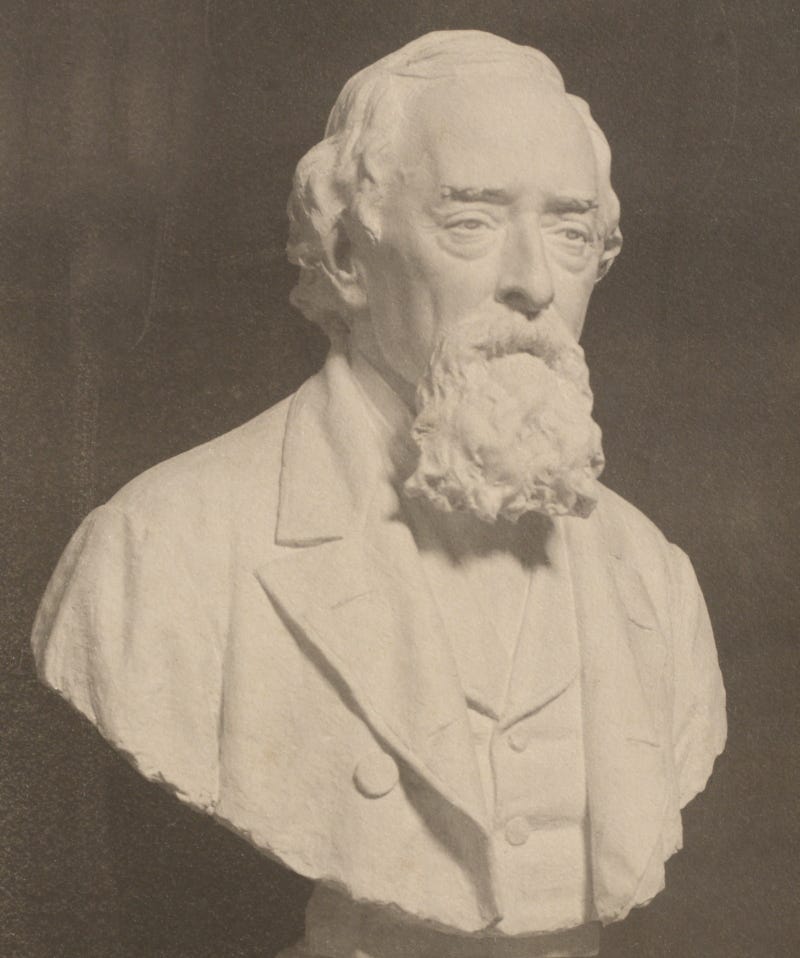

Basevi’s Critiques

Abramo Basevi (1818–85) was an Italian composer, scholar, and musician whose writings on Verdi have sparked debate on opera analysis. His 1859 text, Studio sulle opere di Giuseppe Verdi, provides us with a rigorous examination of all of Verdi’s operas composed till then, except the first two. As a former opera composer himself, Basevi knew better than other critics the mechanisms of composition and earlier 19th century operatic repertoire, which served as a compositional platform. This best places Basevi to provide his more technical criticism of opera in general. The structure of the Studio, as described by Roger Parker, is as follows:

A separate chapter is devoted to each of Verdi's operas from Nabucco to Aroldo, and each chapter typically dispenses with the plot very early, mentions the language of the libretto rarely, and uses much of the remaining space in a blow-by-blow, sometimes rather technical account of each "number" of the score in question.1

Both Parker in his essay and Stefano Castelvecchi in his introduction to his and Edward Schneider’s new translation of Basevi’s text note that Basevi’s failure as a composer might lead to envy-induced bias in his assessment of the composer whose fame eclipsed his own.2 However, as Castelvecchi notes, Basevi is quick to attack Verdi and to appreciate him too, depending on his understanding of Verdi’s technique. Consider his general praise for Rigoletto:

Verdi was truly inspired in setting this drama, which completely accorded with his vigorous way of feeling, always in search of contrasts.3

And a critique of a Macbeth chorus:

The witches’ chorus that opens the third act is long and, with the exception of a few measures at the beginning, lacking in character. The end, in the major mode, by no means expresses, even to the least degree, the fierce joy of these evil beings. See how Meyerbeer succeeded in fitting music to demonic joy in the celebrated Infernal Waltz from Robert le diable.4

Basevi’s objectivity renders his account reliable as a mostly impartial observer, and also renders insight into his musical preferences. We know what Verdian features he considered ‘good’ music, what was ‘old’, and what was a musical innovation.

This analysis spotlights Basevi’s theory of musical form. To Basevi, “forma” does not refer to an underlying theory explaining an opera as an organism consisting of various ‘numbers’ or movements. “Forma”, rather, is much more microscopic. Basevi is talking about the structures, or rather sub-pieces, of tools which build up operatic numbers.5 Of course, there are exceptions, as Parker notes, but these are geared towards later operas like Rigoletto, La Traviata, and Simon Boccanegra. In these, Basevi’s use of “forma” is more Germanic, more macroscopic– he is referencing operatic movements themselves, and not their building blocks.6 There might even be a tinge of musical organicism in Basevi’s descriptions– the idea that these more recent (for Basevi) operas are not an agglomeration of numbered movements, but a designed unity each.

Austro-German Theories

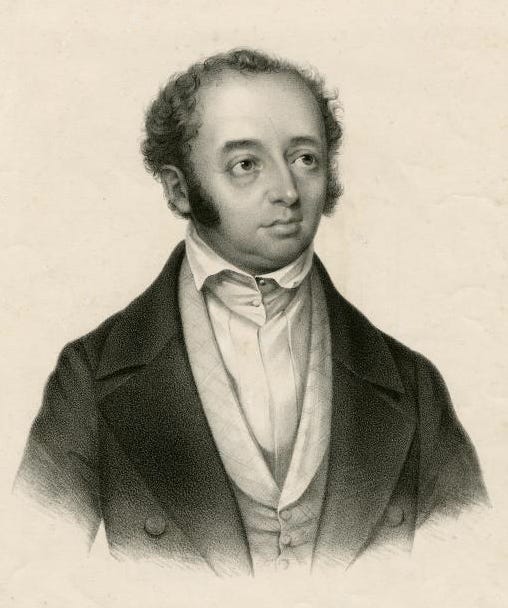

Northern European conceptions of form were much more firmly rooted in philosophical abstracts rather than musical or empirically observable nitty-gritties. While Mme. De Staël and the publishers of Il conciliatore lamented the sorry state of Italian literature and opera, German connoisseurs of music marveled at Ludwig van Beethoven’s(1770–1827) apparent rift between the realm of the senses and the realm transcending the senses. The music critic E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), for example, found a romantic model in Beethoven:

Romantic taste is rare; even rarer is romantic talent, and it is for that reason that there are so few who know how to strike up the lyre that unlocks the wondrous realm of the infinite. Haydn romantically grasps the human in human life; he is more commensurable with the majority. Mozart draws upon the superhuman, the miraculous that dwells in the inner spirit. Beethoven's music sets in motion terror, fear, horror, pain and awakens the infinite yearning that is the essence of romanticism.7

Hoffmann had received the score of Beethoven’ Fifth Symphony in 1810 and was enamored by the grand smattering of mystery and suspense across the musical canvas, finding it beyond the limitations of mere experience.

This relationship came at the forefront of German music theory in the 19th century. The theorist Adolph Bernhard Marx (1799-1866) was steeped in the Hegelian notion of “the history of music as the progress toward one synthesizing and culminative goal.”8 Beethoven’s music was simultaneously such an “end point”, the culminating goal of music up to then, as well as a “new era” of how theorists approached musical form. Post-Beethoven, Romantics understood ‘form’ in its most raw, Platonic definition: each composition had a fundamental, perfect idea in abstraction; composers’ job was to realize that idea through their music while theorists’ was to examine its origin in the ideal realm. Composers realizing these abstract ideas into music which struck its audience’s passions would be akin to Moses descending from Mt Sinai with the Ten Commandments, the physical manifestation of the metaphysical Word of God.

This grandiose theory of the becoming of music does not preclude smaller-scale musical structures entirely. While German notions of form might not resemble a Basevian breakdown of the framework of a particular stretto, cavatina, or tempo d’attacco in a Verdian number, Marx himself espoused a conventional and an innovative understanding of form. Kunstform and Form differ: “whereas Kunstformen is Marx's term for the conformational, that is, the basic formal patterns shared by a large number of individual works, Form is the manner in which "the content of the spirit has been determined ... [and] made comprehensible to the understanding."”9 Thus, Marx views form as a precondition to music’s existence; music cannot come into being without a ‘spirit’. The art of composing is then the process of realizing the content of this spirit. Imagine a blueprint showing the perfect, ideal depiction of a house. The skill of the architect lies in building as close to perfect a house as possible.

Moreover, the conformational Kunstform and innovative Form do not necessary contradict each other for Marx. His opening question itself attempts to bridge an apparent divide between abstract form and conventional content:

In general: how can one speak of form in art as of something that exists for itself; how can form and content be separated, since the characteristic essence of art rests precisely in its revelation of spiritual content — the Idea — through material embodiment?10

Marx opens his section on the fundamental forms again trying to reconcile ideal form and the ontology of a piece with observable, pre-existing material:

The first necessity is this: that the spirit, in order to reveal itself in music, seizes upon musical material. […] Only the succession of two or more tones (chords, rhythmic events, etc.) shows the spirit persisting in the musical element.11

Later, in describing his fundamental forms (Kunstformen), Marx very carefully avoids dubbing the Gang or the Satz, the grassroots of musical structure, as merely bricks in a wall. These may be the elements around which musical structure is built, but they are in no way independent of each other or mere blocks which can be added or removed from a composition. To Marx, they come into being relative to each other, evolving, mutating, and adapting in accordance with the ontological underlay of the composition.

And all our building blocks are ready. Stay tuned until next week when we shall finally construct the German-Italian nexus by showing the epistemological similarity between Verdi’s operas and Austro-German theories of form, while underscoring their socio-culturally Italian ontology.

References

Basevi, Abramo, Edward Schneider, and Stefano Castelvecchi. 2013 (1859). The Operas of Giuseppe Verdi. Edited by Stefano Castelvecchi. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Cassedy, Steven. 2010. "Beethoven the Romantic: How E. T. A. Hoffmann Got It Right." Journal of the History of Ideas (University of Pennsylvania Press) 71 (1): 1–37.

Marx, Adolph Bernhard. 1997 (1856). "Form in Music." In Musical Form In the Age of Beethoven: Selected Writings On Theory and Method, edited by Scott Burnham, 55-90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parker, Roger. 2014. ""Insolite Forme", or Basevi's Garden Path." In Leonora’s Last Act : Essays in Verdian Discourse, by Roger Parker, 42-60. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 1995. "Form as the Process of Becoming: The Beethoven-Hegelian Tradition and the ‘Tempest’ Sonata." Beethoven Forum (4): 35-71.

(Parker 2014, 49)

(Basevi, Schneider and Castelvecchi 2013 (1859), xv-xvi)

(Basevi, Schneider and Castelvecchi 2013 (1859), 163)

(Basevi, Schneider and Castelvecchi 2013 (1859), 97-98)

(Parker 2014, 51)

(Parker 2014, 52)

(Cassedy 2010, 6)

(Schmalfeldt 1995, 42)

(Schmalfeldt 1995, 44)

(Marx 1997 (1856), 56)

(Marx 1997 (1856), 66)